~The Ethics of the Lost, Toward the Limits of Poetic Language’s Potential~

Contents

◆Reflections: The Song of Wanting to Be Human(NINGEN NI NARITAI UTA)

◆From Rock to Idols, and Then to Girls Band Anime

- “Britain in the 1960s: From the Beatles to Thatcher,” and Then to AMVs

- From AMV to Girls Band Anime,

A Return to Girls Band Anime Through Idols - BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!! Pre-BanGDream! and “Everyday Life” Anime,

Or Music as Festival

SHOW BY ROCK, Zombieland Saga, BanGDream! (Pre-It’s MyGO!!!!!) - Reinterpreting “Slice-of-Life”

◆ The Ethics of Being Lost - Defining Lostness

- The Philosophy of Lostness: Kierkegaard

3-1. The Philosophy of Lostness: Laozi’s “Tao”

3-2. The Philosophy of Lostness: Laozi’s “Tao” - “Lostness” in BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!

◆Poetic Language in Music - The Origin of Poetic Language: Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin of Languages”

2-1. The Role of Poetic Language: Mallarmé’s “Notes on Language”

2-2. The Role of Poetic Language: Roman Jakobson’s “Poetic Function” and the Principle of Repetition

◆Poetic Language and “Le Sémiotique” - Julia Kristeva, The Revolution in Poetic Language

- “The Semiotic Impulses of Dickinson’s Poetry and Their Medicinal Virtues”

(Original Title: “THE SEMIOTIC PULSIONS OF DICKINSON’S POETRY AND THEIR MEDICINAL VIRTUES”)

◆Poetic Language in BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!! - Spring Shadow(HARUHIKAGE),

Azure Sky Running Beside(HEKITEN BANSOU) - Poem (Uta), Poem Super Bond

(UTA KOTOBA) - Lost Star Cry(MAYOI UTA),

Lost Path Days(MELODY)

◆Toward the Limits of Poetic Language’s Potential

◆Overall Review of All Episodes

◆References

◆Reflections: The Song of Wanting to Be Human(NINGEN NI NARITAI UTA)

(From BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!! Episode 3)

“I made friends like everyone else

But even when I’m with them, I feel alone

I want to live like everyone else

I want to be human“ (MyGO!!!!! ”Song of Wanting to Be Human”

(NINGEN NI NARITAI UTA))

When you didn’t feel the same as others.

When you couldn’t fit in with people.

When you couldn’t understand others’ feelings.

Can you imagine the terror of feeling out of sync with the world?

The opening four paragraphs are the first poem and first lyrics

of BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!’s protagonist:

Takamatsu Tomori.

From the story’s beginning, she struggles “not to drift from the world,”

loses friends, fails to gain her mother’s approval,

and writes these words mindlessly, wandering aimlessly.

The overwhelming resolution of this solitary craftsmanship left me dizzy.

I felt myself present here.

Yet I grew uneasy. Crafting a story with this model would prove exceedingly difficult.

No easy solutions, no conventional breakthroughs—

only a long, arduous journey through darkness lay ahead.

And then it betrayed me. In a completely unexpected way.

This paper first surveys the history of girls’ band anime.

It then defines “lost child” and contemplates the “ethics of being lost.”

As part of this ethics, it reexamines poetic language in music

and discusses the core concept of “Le Semiotic.”

And when we reach the very edge of poetic language’s potential,

we will likely glimpse the core of this work’s potential.

To anticipate the conclusion: as a “lost child” without “wandering,”

it will continue to question possibilities over an extremely long range.

※The OP and ED will likely be the deciding factor. Please refer to them.

OP: HiToshizuku (MyGO!!!!!)

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/_CraJ8654Bg

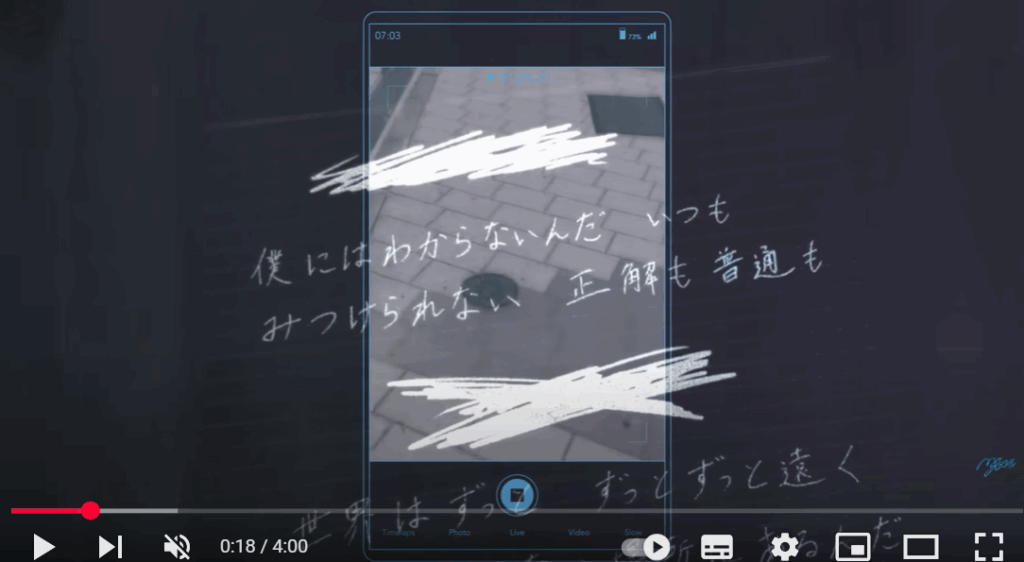

ED Shiori (MyGO!!!!!)

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/fXk4czRGl4E

※The sequel to this work, “BanGDream! AveMujica,”

will be the ultimate masterpiece among anime broadcast in the winter and spring (first half) of 2025,

a work destined to carve its name into the annals of girls’ band anime.

Through both works, the attitude toward music serves as a direct metaphor for the attitude toward humanity,

and a declaration of one’s stance toward the world.

I find comparing them to be extremely interesting.

◆From rock to idols, and then to girls’ band anime

(Image)

※See also the previous article

- “Britain in the 1960s: From the Beatles to Thatcher,” and then to AMV

In the modern era, rock bands and idols employ marketing strategies—such as how they sell music and organize events—to pursue maximum commercial success. By leveraging media exposure, specifically television, interviews, and social media, both groups deliver their messages to a broad audience.

For example, Takashi Koseki’s “Britain in the 1960s: From the Beatles to Thatcher” (Chuko Bunko) focuses on the Beatles and British history surrounding them. Regarding his arguments about the Beatles/rock, the idol/rock ‘n’ roll/rock issue can largely be traced back to US/UK relations during the Cold War era.

According to this book, the “unconscious rock singer” belongs to the idol lineage derived from American show business.

Prototype rock ‘n’ roll represents a break and leap from American folk music (gospel, country, R&B, etc.), though this also involves issues of race between blacks and whites.

The broad concept of “self-conscious subculture” in rock music can be explANONd as a derivative of the Beatles.

Moving forward in time, in Japan, the period of the 1980s—the era of idol anime creation and pop music integration—becomes the subject of examination.

This flow began with Godiego’s ending theme for the 1979 theatrical release of Galaxy Express 999,

and is represented by works like 1982’s Macross, 1983’s Cat’s Eye, and Creamy Mami.

At the time, anime’s low standing within the cultural scene was fundamental,

resulting in songs like TM Network’s early “your song” often going unnoticed.

Other examples include the Pillows’ “FLCL” from the 1990s AMV (Anime Music Video) era.

Even in the late 1990s post-EVA(New Era Evangelion) era, the age of late-night anime, the distance between subculture and anime did not significantly narrow.

Since then, the turning point of the 2000s would include “FLCL” & Pillows, the animation community,

AMVs, links to overseas markets, etc.

For example, the Japanese film “Linda Linda Linda,” which reinterpreted the meaning of The Blue Hearts’ “Linda Linda Linda” as an “affirmation of everyday life,” became a meta-expressive attempt influenced by subsequent works like “The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya” and “K-ON!”.

Simultaneously, the high quality of AMVs (Anime Music Videos) for “The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya” and “K-ON!” contributed to their emergence as band music anime, marking the beginning of their expansion into the global market.

(Yoshiharu Ishioka)

- From AMVs to Girls Band Anime,

A Return to Girls Band Anime Through Idols

(Image)

(Quoted from Tokuda Yori’s “BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!! Achievement: From Idol Maturity to the Great Girls Band Era”)

For instance, many commentators have pointed out the common ground between “Love Live!” (2013) and “K-ON!”, two iconic idol anime of the 2010s. K-ON!, one of the greatest masterpieces of the “slice-of-life” genre, depicted the affirmation of the “loose connections of this very moment” common to works in this genre, set to rock music. It revolutionized the nature of music anime and the treatment of anime voice actors within the music scene. Critic Tsunehiro Uno, finding parallels with the live-action youth film Linda Linda Linda (2005), went so far as to argue that K-ON! “rewrote the meaning of rock.” It shifted from being a “symbol of anti-authority” that had lost its enemy to a straightforward “affirmation of the everyday.” Rock music was renewed by After School Tea Time.

By the 2010s, this merged with the “live idol boom” spearheaded by groups like AKB48 and Momoiro Clover Z, leading to a proliferation of music anime centered on idols. A symbolic work was Love Live!, frequently compared to K-ON! due to shared staff (like scriptwriter TomoTatsuki Hanada). The “club activity” settings like “light music club” and “school idol” proved particularly well-suited for expressing the fleeting nature of “everyday life” and “youth.” Furthermore, the staging that heightened the unity between performers and audience at idol live shows, combined with the “irreversibility of career formation” inherent in idols (primarily teenagers), created a synergistic effect that amplified this fleeting quality. Idols thus became exceptionally well-suited to singing about the affirmation of “this very moment’s everyday life.”

The irreversibility of idols’ career paths synergistically enhances their ephemerality, making them uniquely suited to sing about the affirmation of “this very moment’s everyday life.” Conversely, during the 2010s, particularly the first half, idols sometimes functioned as icons for ‘reconstruction’ and “town revitalization.”

This image of idols as affirming “this very moment” is reflected, for example, in the lyrics of songs by μ’s, the idol group formed in the anime Love Live!.

Miracle, it’s right now, right here

This place where everyone’s feelings led us

So truly enjoy this moment

A story we all make come true, a dream Story

(KiRa-KiRa Sensation!)

While “everyday-life” works are sometimes called “airy-feel” and the two are treated as nearly synonymous, the affirmation of “everyday life” by idols built an era, so to speak, filled with “passion.”

(End of quote)

Then, as the 2020s arrived, girls’ band anime began showing signs of a resurgence, seemingly countering the decline and regression of idol culture (including anime).

Examples include “SHOW BY ROCK,” which began in 2013; “BanGDream!,” which started its series in 2015; “Zombieland Saga” in 2018; and “Bocchi the Rock!” in 2019 (manga; anime adaptation in 2022).

- “BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” and the earlier “BanGDream!” vs. “slice-of-life” anime, or music as celebration

(Image)

What each series shares is a musical “connection” that affirms everyday life as a kind of “celebration.”

In the aforementioned “SHOW BY ROCK,” while Sanrio’s uniquely absurd gag sense shines through, crises are fundamentally resolved through music (such as Cyan using a song performance to gloss over Retrie’s dissatisfaction with the band members’ skills).

Similarly, “Zombieland Saga” is a masterpiece where Cygames’ original concept, MAPPA’s superb direction, and AVEX’s skillful music delivery bring catharsis. It depicts the tragicomic existence of idols transformed into zombies to revitalize a declining region, yet fundamentally affirms the connection forged through music. (Personally, I appreciate the metafictional elements in the sequel, “Zombieland Saga Revenge”—such as how the idols’ activities at the disaster site evoke AKB48’s post-Great East Japan Earthquake recovery live performances.)

BanGDream! also follows a basic structure where the celebratory nature of the music itself fundamentally affirms “connection,” “thrill,” and “sparkle” from the first generation up until Molfonica. Notably, in the 1st season, Kasumi’s somewhat reckless pursuit of sparkle was counterbalanced by Saya’s family circumstances, seemingly introducing conflict (Episode 7 is a standout). However, this conflict subsequently dissipated, leaving music fundamentally affirmed.

BanGDream! 3rd, which expands on the peculiar tension in BanGDream! 1st’s finale, depicts a dogmatic band breakup crisis centered around Raise A Suiren’s leader Chuchu. Yet, fundamentally, music is still affirmed. Or, in “BanGDream! Molfonica,” the unconditional affirmation of music seemed to retreat (the vocalist role couldn’t sing due to conflict over lyrics), but ultimately, it was portrayed positively.

- Reinterpreting the “Everyday Life Genre”

(Image)

(Quoted from Tokuda Yo’s “Achieving BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!: From Idol Maturity to the Era of the Great Girls Band”)

While “slice-of-life” works are sometimes called “air-like” and the two terms are often treated as synonymous, the affirmation of the ‘everyday’ by idols built an era brimming with “passion.”

However, as SNS society progressed, structural problems within the idol industry began to be pointed out. For example, as Takashi Kazuki noted, the situation where even idols’ “private posts” (effectively indispensable as fan service) were consumed as content came to be recognized as posing labor issues. Kazuki critically analyzes this structure as “documentaries becoming everyday life.” Precisely as a problem lurking within “everyday life,” idols face the contradiction that if they self-referentially broadcast their “everyday” lives, that very ‘everydayness’ collapses (being reclaimed as “labor”).

A dilemma emerged where two discourses coexisted: “Only through idols can ‘everyday life’ be affirmed” and “As long as idols strive to remain idols, their own everyday lives are lost.”

The anime film Trapezium (2024), based on an original work by Nogizaka46’s first-generation member Kazumi Takayama, serves as a straightforward indictment of this issue (which has expanded beyond idols) from the perspective of an idol. High school girl Yū Higashi, who dreams of becoming an idol, is acutely aware of the problem of “documentaries becoming normalized.” She deliberately participates in volunteer activities as “staged performances,” posting footage on social media, and her life is depicted in a deliberately self-indulgent manner as she navigates a daily routine deemed “desirable for an idol.”

It is suggestive that Trapezium was adapted into an anime in the 2020s. The fact that this phenomenon is now being meta-referenced even within the anime world—where “documentary-like portrayals of everyday life” are not problematized in the same way as in reality—symbolizes the genre’s maturation (≈ transition period).

(End of quote)

So, what ethical principles and practices did this work, BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!, employ to create new music? Let us begin by considering the ethics of its central theme: “being lost.”

◆The Ethics of Being Lost

(Image)

- Definition of Confusion

What is being lost? What is confusion?

Literally, it means bewilderment and disorder. Etymologically, it likely originates from a language that literally “confuses,” possessing a fundamentally contradictory meaning.

For example, in Shirakawa Shizuka’s Commonly Used Kanji Dictionary, 2nd Edition, “confusion” is recorded as follows:

To be lost means to be confused and disordered. The “Setsubun” (二下) states “to be confused,” and the ‘Gyokuhen’ defines it as “to be disordered,” meaning to be confused and disordered (to be bewildered and disordered). It is read as “mayou, madou, midareru.”

Now, what about the etymology of the “惑” in “惑乱” (confusion/disorder)?

One theory suggests it depicts a halberd guarding the perimeter of a mouth (the shape of city walls surrounding a settlement), with the guarded area being called a domANONnother theory sees it as a limited form of “有” (to have), used like “or.” The feeling of doubting other possibilities, as in “or perhaps,” is called惑 (moyo), meaning “to doubt, to question, to suspect.”

Similarly, what about the etymology of the word “乱”?

The original character was formed by combining the radical part of 亂 (unconvertible in kanji conversion) with 乙.

乙 represents the shape of a bone spatula. The radical part of 亂 consists of H (the shape of 冂, a thread-winding spindle) with 么 (yō, thread) placed over it. Since the thread is tangled, hands (the upper part is a claw, the lower part is a fork; both represent the shape of a hand) are added above and below, forming the shape of someone trying to untangle it, thus conveying the meaning of “to become disordered.” Using a bone spatula to untangle and fix this disordered thread is called “亂,” meaning “to settle” or “to restore order.” While the radical part of 亂 means “to become disordered” and 亂 itself means “to settle,” later usage mistakenly added the ‘disorder’ meaning to 亂. Consequently, 亂 came to be used for both “to settle” and “to become disordered.”

If “to be lost” is defined this way, how did questions about being lost develop?

This likely overlaps with the history of ethical inquiry. Next, while referring to the philosopher Kierkegaard and Laozi, I would like to consider what kind of “ethics” might exist.

- The Philosophy of Being Lost: Kierkegaard

(Image)

The philosopher Kierkegaard focused on the conflict between “doubt” and “decision” concerning one’s own existence.

He stated, “What I lack is the resolve to decide what I ought to do,” making the discovery of one’s own idea (standard for living) amidst doubt the central task of philosophy.

He also believed human existence consists of three stages: “aesthetic existence,” “ethical existence,” and “religious existence.”

Anxiety, according to Kierkegaard, is what propels the leap from the second stage, “ethical existence,” to the third stage, “religious existence.”

When humans strive for freedom, an unfree reality emerges.

Even when attempting to abandon oneself to practice an ethical way of life, ethical existence reaches an impasse because the act of abandoning oneself is also performed by the self.

There, the only way forward is to sever the self through God’s power, liberate the self incapable of ethical living, and receive the free self from God.

It is “anxiety,” the fundamental human mood, that propels this leap.

Urged on by anxiety, humans leap from ethical existence to religious existence.

Anxiety can be considered in various stages, but its peak is a way of life that closes oneself off from God and retreats into oneself, which I believe plunges people into profound anxiety.

The greatest anxiety is death, and I consider the death of the spirit that continues after death to be a greater problem than the death of the finite body. And to overcome physical death, one must turn one’s gaze toward the meaning of life.

However, humans are not given a purpose for living that serves as a standard for how to live.

Consequently, they are perpetually exposed to the anxiety of life, constantly searching for a purpose to anchor themselves,

leaving humanity in a state of perpetual despair.

Kierkegaard’s conclusion is that this despair can only be resolved through faith in God.

In “BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!”, the protagonist, Takamatsu Tomori, is tormented by anxiety and tries to withdraw into herself (by not playing in the band, becoming fixated on inanimate objects (non-human), and writing words in her notebook).

But ultimately, what she chose was not “God”.

3-1, The Philosophy of Doubt: Laozi’s “Tao”

(Image)

Laozi’s philosophy is succinctly expressed through the concepts of “Tao” and “Wu Wei Ziran” (non-action and naturalness).

‘Tao’ embodies the idea that “all things are one.” It is the cosmic principle that gives birth to all things, representing the natural order that transcends artificial distinctions and conflicts. Laozi taught that everything functions harmoniously when aligned with this principle. Famous is “wu-wei ziran” (non-action and naturalness), which values the state of being as it is, without artificiality. “By doing nothing, one actually accomplishes everything.”

(Quoted from “Laozi: A Gateway to the Wisdom of Chinese Thought” by Wang Yuechuan, translated by Nozomi Ueda)

The “Tao” can be described as a metaphysical existence distinct from ordinary things—seeming to exist yet not, seeming not to exist yet present. Things are truly elusive and hard to grasp. Though elusive and hard to grasp, within them lies form. Though elusive and hard to grasp, within them lies substance. Like a shadow, dim and faint, yet within it lies essence. This essence is purer than anything else, and within it lies proof.

Even when you strain your eyes, you cannot see it, so it is called the slippery one. Even when you strain your ears, you cannot hear it, so it is called the faint one. Even when you touch it with your hands, you cannot grasp it, so it is called the most minute one. These three things cannot be further refined; they blend together as one. When it is above, there is no brightness; when it is below, there is no darkness. It flows on and on, indescribable, returning to the void. It is called the formless form, the unseen image, the indistinct, the “something-like.” Face it head-on and you cannot see its face; follow it and you cannot see its back.

Yet, if one firmly grasps the ancient “Way,” one can control what exists now and know the ancient, that is, the beginning of all things. This is called the root of the Way. Within it lies the form, within it the substance—a formless state, an invisible form. This material substance is an eternal existence beyond human will, operating everywhere and ceaselessly. Thus, it can only be named “the Way.”

3-2, The Philosophy of Doubt: Laozi’s “Tao”

In truth, the “Tao” here is an abstract absolute—the root of all existence, the primordial driving force and creative power within the natural world. It describes the process by which this “Tao” creates all things, ceaselessly descending from the most abstract essence into the material world to take concrete form and bring forth all beings. This is precisely what Laozi Chapter 40 states: “All things under heaven are born from ‘Being’. ‘Being’ itself is born from ‘Non-Being’.” The birth of all things from the “Tao” is a process from “few” to “many,” contemplating that all things are born only from nothingness. “Non-Being” is the “Tao,” and since ‘Being’ can be born from the “Tao,” the Tao itself becomes the unity of non-being and being.

Beyond meaning discipline of action and ultimate substance,

“Tao” also carries a linguistic sense.

Thus, the Tao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Tao.

The Tao that can be spoken of is the Tao that can be put into words,

closely linking Tao and language.

Human language has its limits, and clinging to these limits will lead one astray in the process of recognizing the Way.

Yet, it is precisely the inexpressible words that can represent the indescribable “Way.”

Words may be the “cage” of thought, yet we can only speak through that “cage of words.”

Words possess duality—they are both concealment and revelation. Laozi himself stated, “The right words sound contrary to truth,” and “Retreating is the movement of the Way.” (End of quote)

The true “Way” emphasizes the beauty of the essence, emphasizes the beauty of chaos,

and rejects superficial color beauty or music.

Within this aesthetic of the “Way,” we can likely find the ethics of “wandering” as ‘retreat’ and “chaos.”

Metaphysical though it may be, it is precisely within the “unspeakable word” that the “ethics of being lost” resides.

Based on this ethics, I wish to consider the “wandering” within “BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!”.

- The “Wandering” within “BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!”

(Image)

(“BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” Episode 3)

Let us return to “BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” (hereafter referred to as “MyGO!!!!!”).

What exactly is the “doubt” depicted in this work?

Simply put, it is a counter to the “impossibility of everyday life,”

and a counter to the “impossibility of music.”

(Image)

(“BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” Episode 4)

This is likely symbolized by the protagonist, Takamatsu Tomori’s, “undifferentiated” character development.

An abnormal fixation on non-human entities—inorganic matter, animals, artificial objects.

Tomori’s room, where he maniacally organizes his collected items with meticulous order.

His fixation on insects and stones startles and terrifies his friends,

and even his mother, through a wry smile, refuses to understand him.

Now in middle school, he still fixates on inorganic objects, writing his misunderstood feelings in a notebook—a behavior reminiscent of early childhood, neutral, undifferentiated, lost.

※Incidentally, the introduction of “stray cat” RaNA as a catalyst exposing all band members’ “undifferentiated” nature should also be considered, though that merits separate examination.

Yet she delves into this “undifferentiated” state through language.

“My poetry is the cry of my heart!”

In the early stages, this manifests as self-referential songs celebrating everyday miracles, like the previously quoted μ’s tracks or the K-ON! insert songs “Gohan wa Okazu” and “Tenshi ni Fureta yo!”, with “Haruhi Kage” presented as the lyricist.

(Image)

Through the clouds, sparkling, sparkling

Filling my heart, overflowing

Before I knew it, my cheeks, sparkling, sparkling

Growing hot, hot, wet

Why are your hands so warm?

Hey, please, I beg you, don’t let go now (MyGO!!!!! “Haruhi Kage”)

(Quoted from

‘BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!’ Achievement: From Idol Maturity to the Great Girls Band Era | Tokuda Yo)

“Haruhi Kage” was composed by the junior high school band CRYCHIC, with vocalist Takamatsu Tomori singing about her bonds and gratitude towards the members. Tomori, who was tongue-tied, “airheaded,” and struggled to fit in, first felt friendship with others through band activities, pouring those feelings into the lyrics of “Haruhi Kage.”

However, immediately after “Haruhi kage” is performed,

some form of “breakup” inevitably occurs.

Right after CRYCHIC played “Haruhi kage” and successfully completed their first live show, band founder Sakiko ToyokawANONxplicably vanished. A few days later, Sakiko appeared at the studio soaked to the bone in the rain, without even an umbrella. She suddenly declared her departure from the band. Drummer Tatsuki denounced Sakiko as irresponsible, but bassist Soyo calmed him down. Soyo asked everyone around her if it made sense to disband, insisting they should all have enjoyed being in this band. Then guitarist Mutsumi answered.

I never once thought this band was fun.

Soyo is speechless. CRYCHIC effectively disbanded. Time passes, and the scene shifts to when they were first-year high school students—

This is the scene depicted at the beginning of “Episode 1.”

(Image)

(“BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” Episode 1 Opening)

In Episode 7, “Haruhi Kage” is performed once more, yet it still fails to affirm the bonds of everyday life. The band activities resume with former CRYCHIC members Tomori, Tatsuki, and Soyo joined by new members ANON and RaNa (later officially forming “MyGO!!!!!”), and the scene depicts their long-awaited first live performance.

Though Soyo, still holding onto feelings for CRYCHIC, had firmly positioned “Haruhi Kage” as merely a practice song, during the actual performance, RaNa spontaneously begins playing the intro phrase of “Haruhi Kage,” and the song starts playing almost by default. Forced to join in, Soyo then spotted Sakiko, who had coincidentally come to the venue. Witnessing “Haruhi kage”—a song that once symbolized CRYCHIC’s bond—being performed by another band, Sakiko burst into tears and ran out of the live house. After the show, Soyo lashed out at the members and stopped showing up for band activities.

(Image)

(From the final scenes of “BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!” Episode 7 ”Why You all did Play Haruhi kage!?””)

Sayo’s outburst immediately after performing “Haruhi Kage” is frequently discussed by viewers both domestically and internationally (especially in China).

In “It’s MyGO!!!!!,” the affirmation of “everyday connections” through band performances inevitably fails. In fact, one could even say that the very act of “self-referential affirmation of the everyday” becomes the cause of the everyday itself collapsing.

This is also reflected in the visual direction of Episode 7. The episode depicts the members’ backstage moments right up until the scene immediately before the live performance, shot from a fixed camera angle with no background music. Director Hirotaka Kakimoto stated he wanted to capture “MyGO!!!!!’s natural interactions.” Through this fixed-camera, “documentary”-style angle, natural interactions—that is, their “everyday” selves—were depicted.

Yet immediately afterward, they face the “collapse of connection.” Here, the opposite of what happened when Love Live! inherited K-ON!’s legacy occurs: the story begins precisely with the failure to ride the wave of music with that everyday mentality.

As the “idol genre” reaches maturity, the “affirmation of the everyday” inherited by music anime is increasingly depicted as something difficult to achieve. Let us call this the “impossibility of the everyday.” And it is in this sense that the scope of music anime is challenged: how should it confront this “impossibility of the everyday”?

(End of quote)

So, how can the “everyday” be affirmed?

In this work, “MyGO!!!!!,” it is expressed through poetry reading—that is, as poetic language.

Reexamining the potential of poetic language as a precursor to language itself

could become the “ethics of the lost”—the ethics of “MyGO!!!!!”.

Taking a detour, let us confirm the origins and role of poetic language in music,

the framework surrounding poetic language,

and then return to “MyGO!!!!!”.

◆Poetic Language in Music

(Image)

- The Origin of Poetic Language: Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin of Language”

The first language was “poetic,” driven by passion (emotion) rather than desire.

(Various theories exist. From Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Discourse on the Origin of Language”)

Early language was metaphorical and evocative, existing as the “language of poets” to convey emotion and passion before rational, logical language.

The first language is said to have possessed melodic and musical qualities, with language and music considered one.

From a Romantic perspective, primal poetic language—such as the “cry of nature” or the “poetry of the people”—was emphasized.

In “The Origin of Language,”

while initially establishing language as a means to convey thought,

it is interesting that

the final chapter, Chapter 20, “The Relationship Between Language and Political Systems,”

depicts how modern people struggle to effectively convey meaning through language.

Thus, The Origin of Language begins with an examination of how thoughts are conveyed,

only to conclude with an examination of how thoughts fail to be conveyed—a structure that is, in a sense, paradoxical.

(Quoted from “On the Origin of Language”)

There are only two general ways we can influence another’s senses: action and voice.

The effect of action is either direct through touch or indirect through gesture.

The former [the effect of actions] cannot be transmitted far, limited by the length of the arm,

while the latter [the effect of gestures] reaches as far as the gaze.

Thus, among scattered people, only sight and hearing remANONs passive organs for language.

Since emotion was humanity’s first motive for speaking, humanity’s first expression was figurative language.

Metaphorical speech arose first; literal meaning was discovered last.

Things were only called by their true names after people saw them in their true form.

People spoke only in poetry at first. The idea of speaking theoretically came much later.

Poetry was discovered before prose.

This was only natural, for passion spoke before reason.

The same held true for music.

At first, there was no music beyond melody, no melody beyond the varied sounds of spoken language.

Inflection shaped song, and pitch shaped rhythm.

People spoke through sound and rhythm as much as through syllables and voice [vowels]. (Omitted)

Poetry and eloquence share the same source; they were originally one and the same. (End of quote)

※Incidentally, the aporia mentioned at the outset is that philosophers stripped language of its musical elements, resulting in the loss of rhetoric from modern language = thoughts can no longer be conveyed.

So, what role did this “poetic language,” born of such origins, come to play in conveying emotion and passion?

2-1, The Role of Poetic Language: Mallarmé’s “Notes on Language”

(Image)

Poetic language transcends mere meaning, bringing readers new sensations and insights through sound, rhythm, resonance, and structure.

(Quoted from Mallarmé’s “Notes on Language”)

First, the meaning of words differs; then, their tone (ton) differs. There is novelty in the tone a person uses when speaking.

We take the tone of conversation as the final boundary to uphold, the last boundary to keep science at bay. That is, we take it as the cessation of the vibratory range of our thought.

Ultimately, words possess multiple meanings (otherwise people would always understand each other) — we intend to make use of this. And when words are pronounced by the inner voice of our spirit, which has repeatedly consulted past writings (science, Pascal), what effect do they produce concerning their primary meaning? If that effect differs from the effect words produce on us today, we intend to study it. (OC1, p.508)

What this means is that as the meaning of a word changes, its intonation changes accordingly; thus, new meanings and nuances decisively emerge within these intonational shifts. From a linguistic perspective, meaning is indeed more prone to change than sound. This is precisely why phonetic correspondences can be verified.

(From : A Preliminary Study of Mallarmé’s “Notes on Language” by Fumi Tachibana)

To elaborate, the following can be stated: The driving force of language resides not in written language but in spoken language, and specifically within its everyday usage. Consequently, the fiction—the written word—reflected in the conversations of the masses, who are the everyday users of language, is likely significant.

Mallarmé focused on the sensory effects produced by the union of sound and meaning. He depicted the impression of things through the effects they evoked. Here, he conceived of the essential mode of language as “abstraction,” envisioning “poetic language” as the point where language, while an intellectual technique, becomes beauty itself rather than an explanation of beauty.

Before the relationship between words and meaning,

Mallarmé considered the relationship between phonemes and impressions, sensations, and their effects to be crucial.

(Quoted from

(Linguistics for : A Preliminary Study of Mallarmé’s “Notes on Language”

by Fumi Tachibana)

First, we consider linguistic activity in parallel with the epistemological schema of the subject’s apprehension of its object. Then, there is a tendency to seek the origins of poetic language within deviations from this process. Thus, his poetic language is termed “effect” or “mirage,” described as “becoming beautiful” in contrast to mere expression or explanation, and also called “fiction” in consideration of its contrast with the abstraction of the object. (End of quote)

Later, he deliberately relativized concepts like roots and bases, reducing the unit of relation down to the initial consonant, and examined its impression. Here, morphological relations are reinterpreted as semantic relations, yet they do not converge into the analogy of root or base concepts. Instead, they emerge as an uneven bundle of multiple analogical series, extending even into the impressions of onomatopoeia and interjections.

Alternatively, through Heringrath’s textual analysis of Hölderlin, he moved away from traditional hermeneutic methods, revisiting the rhythmic and musical aspects of poetic language and aiming for a linguistic form that focused on the sensory and material properties inherent in language itself. Simultaneously, by focusing on “dissonance, formal tension, discontinuity, abstraction, and the allure of the disruptive,” it would be “that which rejuvenates words, and with them, the soul” (Georg).

Thus, the role of poetic language, in each case, extends beyond mere meaning; through sound, rhythm, resonance, and structure, it brings readers new sensations and insights.

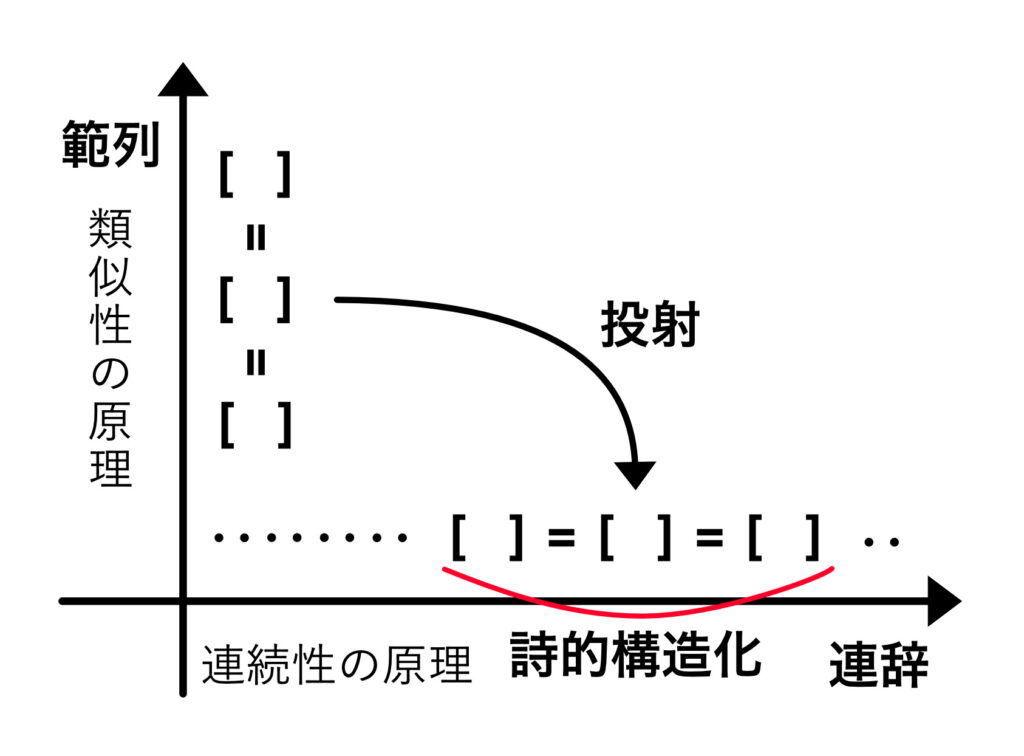

2-2, The Role of Poetic Language: Roman Jakobson’s “Poetic Function” and the Principle of Repetition

(Image)

(https://www.turetiru.com/entry/poetic-function/ Refference)

In What Is Poetry?, Roman Jakobson states that poetic quality emerges “not when words merely indicate the objects they name, nor as an explosion of emotion, but where words are felt as words. Where words and their structure, meaning, external form, and internal form acquire their own weight and value, rather than being indifferent indicators of reality.” At the core of formalist poetics lies the theory of “defamiliarization” (Verfremdung), which aims to shake and renew perceptions automated by the routines of everyday language through the use of alien language.

These are, for example, mechanisms based on the principle of “repetition,” where messages are generated and emphasized through repetition, and this very process is what constitutes “poetic language.” In Saussurean terms, the poetic function is the phenomenon where a “paradigm”—a category of similarities—is projected onto a “syntagm,” a sequence of signs generated as a continuous chain (Asai 2017: 40). The poetic function, based on repetition, emphasizes and generates socially recognized signs through parallelism, symmetry, and contrast, possessing a controlling force that synthesizes their patterns and tendencies.

The origin and function of poetic language can be understood for now.

So, how should we consider its potential for development?

Here, I would like to examine the concept of “le sémiotique” as described by Julia Kristeva.

◆Poetic Language and “Le Semiotique”

(Image)

- Julia Kristeva, The Revolution in Poetic Language

Beyond the traditional framework of semiotics, the concept of “le symbolique” focuses on the process of meaning generation, particularly the creation of meaning within poetic language.

In her major work Revolution in Poetic Language, Julia Kristeva named the symbolic order of language that guarantees the sociality and communication of linguistic activity “le symbolique,” and the state of language where pre-subjective, amorphous bodily drives swirl prior to the symbolic ordering of language “le sémiotique.” Le sémiotique concerns the movement of generation and dissolution prior to all concrete differentiation and formalization, constituting itself as the rhythm of kinetic energy.

The positive effects brought about by “le sémiotique” include the disruption of linguistic order and the liberation of creativity, the activation of non-semantic elements like rhythm and intonation, and the creation of polysemy through the destabilization of subject and object, and of self-identity.

When Le Semiotic connects with poetry reading music, its positive effects include emphasizing the rhythm and sonority of words, expanding the fluctuation of meaning and improvisation, and enabling the direct expression of emotion and the unconscious.

It should be noted that in The Revolution of Poetic Language, “Le Semiotic” is conceived as a language of fragmentation employing the maternal principle against the repression of the paternal principle. Given that the transition from nature (mother) to culture (father) was the normative social and self-reliance perspective at the time, it is worth noting that “Le Semiotic” was viewed with some suspicion. This is because unconsciously employing “Le Semiotic” carries the potential to lead into facile codependent relationships.

Now, regarding “Le Semiotic,” I wish to examine it concretely by referring to Dickinson’s poetry.

- “The Semiotic Impulses of Dickinson’s Poetry and Their Medicinal Virtues”

(Original Title: “THE SEMIOTIC PULSIONS OF DICKINSON’S POETRY AND THEIR MEDICINAL VIRTUES”)

(Image)

This paper demonstrates that Emily Dickinson’s poetry holds significant implications for critical medical humanities, which are open to the interface between language and corporeality. By employing what Julia Kristeva terms a “genotext”—a highly effective and aesthetic linguistic structure—Dickinson conveys pANONnd sorrow, enabling readers and listeners to undergo a process of “liberation from isolation and shared experience.” Through this process, individuals achieve a dual loyalty: loyalty to suffering itself and loyalty to sharing that suffering, rather than sublimating pain into beauty or nothingness through denial.

Dickinson’s poetry presents interpretive challenges to readers through its multilayered meanings, ellipses, contradictions, and the stark contrast between brevity and intense content. This is deeply connected to Kristeva’s concepts of the “semiotic” and the “womb-like space.” Dickinson’s language collapses the “phenotext” (superficial language) used for everyday communication, leading us to a more fundamental human experience.

Furthermore, Dickinson’s poetry functions as a “laboratory” where readers can ‘intuitively’ reconsider human identity, death, and the power of language. Her persistent preoccupation with death and poetic imagery that conceives of death as a “home” particularly evoke readers’ emotional and physical responses, portraying death not as something to be avoided, but also as an object of familiarity and belonging.

The following characteristics can be identified in Dickinson’s poetry:

- Coexistence of meaning omission, suggestion, and contradiction

- Extreme conciseness paired with potent content

- Emphasis on rhythm, rhyme, wordplay, irony, and solitude

・Deviations from traditional poetic forms and an emphasis on the fluidity of identity

These align with Julia Kristeva’s notion that such forms serve as “a crucial means for the depressed and oppressed subject to express and assert itself.” Dickinson’s poetry creates a “democracy of proximity” between reader and poet, establishing a space for profound human empathy distinct from the individualistic capitalist model.

Example:

“A Dimple in the Tomb / Makes that ferocious Room / A Home —” (Poem No. 1522)

A short poem accompanying a letter mourning the death of T.W. Higgin’s daughter, redefining death and loss as a domestic, intimate space.

“dauntless in the House of Death” (Poem No. 339, 1769)

Demonstrates Dickinson’s approach to death, remaining dauntless even in the house of death.

Source Information: – Emily Dickinson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition, ed. R.W. Franklin, Harvard University Press, 2005.

Now, we have explored the possibilities of language through “the ethics of the lost,” “poetic language,” and “Le Semiotic” = the linguistic impulse.

Finally, we wish to confirm that understanding “It’s MyGO!!!!!” through the theory of “Le Semiotic” will likely have a broad scope.

◆BanGDream! It’s MyGO!!!!! Poetic Language in

“MyGO!!!!!” features several original songs performed within the play.

Broadly speaking, these can be divided into two periods: pre-“Poetic Bonds” or pre-“Le Semiotic,” and “post-Le Semiotic.”

- Haruhikage, Hekiten Banso, or Pre-“Le Semiotic”

・Haruhikage (春日影)

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/ZsvJUh03MwI

Regarding the chorus (Kira-Tatsukira-ri), I mentioned it earlier; here I’ll quote the opening lines.

(Lyrics excerpt)

A withered heart, trembling gaze

In this world, I was all alone

Spring, knowing only how to scatter

Coldly dismisses me each year (end of excerpt)

Here lies a world supported by the singer’s own authentic words, beautiful sensibility, and steadfast autonomy.

In the moment of affirming the friend who changed the world during those days frozen in solitude—comparing them to a shining, benevolent heaven—the singer affirms everyday life.

・Hekiten Bansō

(Image)

(Lyrics excerpt)

You’re doing your best, that’s enough

Even if you stumble and fall

You got back up and came here

You’re doing your best, always

Just standing here like this

Is all I can manage (end of excerpt)

It sings of affirming and cheering on the friend (ANON) who shares equal activity, pushing them forward with a brightness that’s two sides of the same coin as frivolity, while bringing back sparkle to everyday life.

Alongside gratitude, we see the budding value here that only the bond of “holding hands” is true—simultaneously acknowledging self-defeat and self-encouragement. Meanwhile, the singer’s self is woven with certain words.

- Poetry, Uta kotoba, or “Le Semiotic”

・Poetry ※Episode 10 Poetry Reading

(Image)

(Lyrics excerpt)

I’m so small

Always a mess

People’s voices sound distant and I can’t hear them

I can’t understand even those close to me

I’m not human (end of excerpt)

Beyond the repetitive phrases like “mess” and “spinning,” the words themselves create a structure that heightens a sense of being lost, beyond just a sensory or self-critical impression.

When reading the passage from “I am not human” through to “The feelings I want to convey always stick in my throat, unable to become sound, so at least I want to leave behind this poem,” the desire to convey “words” themselves—more than the words themselves—becomes overwhelmingly palpable.

・Uta Kotoba

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/wJ-OebTVyvk

The intro’s gentle yet sorrowful guitar arpeggios beginning with “I just don’t understand,”

the B-melody shifting key with “Once again, I’ve broken it,”

the layered, intense drum phrases,

The electric bass and guitar in the chorus, screaming out “Sing, song, sing, now, ah, reach me,”

are the pulsing vitality struggling to rise from the brink of disconnection, revealing a powerful, pre-linguistic stirring.

The affirmation of “a fleeting connection” is expressed not only through the lyrics’ meaning but also as linguistic sound, as “le sémiotique.” The chorus sung as “sing song sing,” where vowels are connected through elision, carries the creation of polysemy at the phonemic level—through rhythm, rhyme, wordplay, the interplay of subject and object, and the fluctuation of self-identity.

This song: The most crucial aspect of “Uta kotoba” within the drama is that, despite being the catalyst that finally allowed them to find “connection” after enduring hardship, it was completed by chance through improvisation and would never be played again.

“Affirmation of daily life” and “connection” have become such distant, unattANONble things.

Alongside phrases like “messy” and “throbbing,” the repetition of “singing song” and other sensory, meaning-transcending phrases embody the very essence of “Le Semiotic” = the linguistic impulse itself. Longing to connect. Laying bare all past joy, sorrow, and mistakes. Transforming into words, transcending words. Wanting to live together, wanting to suffer together, even if our lives never intersect.

- Mayoi Uta, Melody, or After “Le Semiotic”

・Mayoi Uta

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/B8k6JtF6WrU

(Lyrics excerpt)

I can’t blend into the glitz

Ignore this heart of mine

Don’t push for a bright tomorrow

Faint starlight flickering in the night sky

Hesitating, I drift apart

Ah, wandering—that’s me

Becoming me—that’s all

That’s all I can do

I can’t imitate anyone well

(Excerpt ends)

“Flicker,” ‘Sting’—through such repetitive, sensory phrases, it evokes the sensations at the very foundation of language itself, squeezing out the “cry” as its precursor.

“Why dismiss these painful days as mere boredom?

Staggering, yet still struggling.”

Here, “daily life” is utterly severed. It is the trembling cry of life’s source, directed at the suffocating pressure, at the self that senses it, or at the loneliness of someone elsewhere in a similar predicament. The loneliness and hesitation of a singularity unable to be swept along by trends, its affirmation— spun out bit by bit while choosing words carefully—will ultimately give someone in the same situation a push forward.

※Personally, my favorite melody.

It’s also likely a counterattack against BanGDream!’s first “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” (Episode 3).

・Melody

(Image)

https://www.youtube.com/embed/t3W552Aou3c

Repetitive, sensory phrases like “round and round” and ‘moping’ similarly evoke the fundamental sensations underlying language itself, squeezing out the precursor “confusion” just as in Mayoi Hoshi’s work.

Tokuda Shishi’s analysis is particularly insightful and worth consulting.

(Quote

“The Achievement of ‘BanG Dream! It’s MyGO!!!!!’: From Idol Maturity to the Era of the Great Girls Band” | Tokuda Shishi)

Precisely because “everyday life” is impossible as a premise, achieving it entails hardship and leads to a sense of “fleetingness” in the sense that it appears only for an instant. This fleetingness doesn’t stem from the possibility of eventual loss (the finiteness brought by “graduation”),

but rather from the fact that it was lost from the very beginning (at the start of Episode 1), allowing it to rise up only for an instant.

This is precisely captured in the lyrics of “Melody”: “I want to gather those tiny moments.”

(Lyrics excerpt)

Walking while lost, walking while confused

We found ourselves in this maze

Nameless emotions—ah, I hold them close

I want to gather these tiny moments

Even if they’re insignificant, I don’t want to hide them

Even if we’re mismatched, sticking out

With awkward words, we drift apart, passing each other by

Hurting over the hurt we caused

Still, I won’t let go of this hand (end of excerpt)

However, phrases like “while lost” and “while confused” reveal a slight hesitation—a reluctance to state things definitively. This aspect also manifests in the lyrics’ function as “musical notation.”

To delve into the theory, the long vocal note frequently appearing in the quoted chorus is “C#.” In contrast, the instrumental section plays “G” as the accompaniment (chord). Without going into detail [8], placing the high “C#” against the bass note ‘G’ creates a sound that borders on dissonance (though it’s not strictly dissonant). Try playing “G,” “(higher) D,” and “(higher) C#” simultaneously on any piano app or similar tool, and you’ll hear how unstable the sound is.

At the level of the lyrics, there is a desire for “affirmation of connection,” yet at the level of the arrangement, dissonance arises throughout. Or, put conversely, it can be interpreted as a manifestation of resolve: accepting that dissonance (the impossibility of the everyday) arises as a given, yet still holding onto the will for that fleeting “affirmation of connection.” (End of quote)

◆To the Edge of Poetic Language’s Possibilities

(Image)

Poetic language as the center of possibility,

in the state prior to language’s symbolic order: “Le Semiotique,”

produced the disruption of linguistic order and the liberation of creativity,

the creation of polysemy through the fluctuation of subject and object, and the wavering of self-identity.

These are brought about by the emphasis on the rhythm and sonority of words,

the expansion of meaning’s fluctuation and improvisation,

and the direct expression of emotion and the unconscious.

Thought is something so great it becomes the basis of human dignity,

and yet it is terribly foolish and base.

Thought gives nothing certain or solid.

It is in a sense natural that people stake themselves on many uncertainties—such as “voyage” and ‘war’ in 19th-century European novels, or “music” in the present essay.

“When man works for tomorrow and for the uncertain, he acts reasonably.” (Pascal, “Pensées”)

For example, the modern novel, impacted by the shock of early globalization, was guided precisely by gambles like “voyage” and “war.” At that time, the novel contANONd a paradox: the Cartesian proof “I think, therefore I am” instead turned toward the realm of “I am not,” toward the uncertainty external to the subject.

This coexistence of human centralization and decentering, with a similar structure,

may lie at the very edge of poetic language’s potential.

Their words and actions in It’s MyGO!!!!!, along with their poetic language, will continue to question possibilities over an extremely long range. They do so as “lost children” without “hesitation,” constantly re-examining order while fully realizing the effects of “Le Semiotic,” yet avoiding the inherent risk of falling into a “co-dependent” relationship.

This represents, for example, the “last thing left for humans to do” when IT advances like AI continue to replace human activities—painful yet joyful and beautiful.

“Let’s get lost together.”

◆Overall Review of All Episodes

(Image)

※STAFF

Original Work – Bushiroad

Director/Sound Director – Hirotaka Kakimoto

Series Composition – Yuniko Ayana

Character Concept – Hitowa, Kazuyuki Ueda

Character Design – Craft Egg

CG Supervisor – Naoya Okugawa

Modeling Director – Yasuhisa Takeuchi, Hiroshi Terabayashi

Rigging Director – Natsuko Yashiro, Toru Kashiwagi, Yui Matsuda

Color Design – Junko Kitagawa, Mei Ishibashi, Yuka Matsushita

Art Directors – Saho Yamane, Risa Tsushima

Art Setting – Hiroyasu Narita

Director of Photography – Daisuke Okumura

Editing – Hatsumi Hidaka

Music – Junpei Fujita, Jin Fujima

Music Producer – Shuji Yoshimura

Music Production – Bushiroad Music, Ace Crew Entertainment

Planning – Yuki Nemoto, Hirotaka Kaneko, Yoshihiro Usa, Yukiyasu Yatabe, Hiroaki Matsuura

Producers – Hayato Nakano, Fumitaka Kitazawa, Kiryu Kure, Yufumi Kanari, Shuichi Binbo

Animation Producers – Hiroaki Matsuura, Shota Hozumi

Animation Production – Sanjigen

Production – BanG Dream! Project (Bushiroad, TOKYO MX, Good Smile Company, Horipro International, Ultra Super Pictures)

Episode 1: The Mysterious Girl of Haneoka – 90 points

(Image)

Direction: Even if we form a band, it’ll just fall apart again. We avert our eyes from hope, letting our thoughts drift toward transcendence (the cosmos). Even when we reach out, we’re unsure how to extend our hands. This also serves as a metaphor for each MyGO!!!!! member’s isolated universe—their own little world.

Screenplay: CRYTHIC disbands, ANON transfers in, recruitment at karaoke depicts ANON’s perspective of Tomori and CRYTHIC. The sharp Tatsuki severs CRYTHIC, ANON, and TOmori.

Storyboard: The opening reveals their stance toward Sakiko in just three minutes. The frivolous ANON and the downcast Tomori emerge through the words and actions of those around them.

Character Design: Stone-picking, magnet-aligning, band-aids indicate an autistic tendency toward childishness. Tomori, who speaks minimally, weaving only what’s truly necessary, ends up hurting and getting hurt. “Isn’t it better to try hard so you don’t become useless?” Her lighthearted words are actually a form of salvation.

The fixation on stone-picking and space represents an obsession with “certainty” and an escape (e.g., Novalis’s “Blauer Blume”).

Art: Neon-outlined red lights, crowds at intersections, dripping windowsills, rain-soaked asphalt emphasize gloom

Sound: Opening tension supported by bass piano. Rich sound sources overwhelm the ears

ED: “What even is ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary’?” plays at the climax of disconnection. Way too dark lol

MyGO!!!!! members lost in each cut reflect their individual loneliness

The Ethics of Being Lost)

ANON: Obedient to calculated ego. Conforms to social norms

Tomori: Worries about friends. Likes finding things. Strives for sincerity in words over posture

Tatsuki: Seeks conflict, avoids others, depends on Tomori

Soyo: Avoiding conflict stems from self-love

RaNa: Absent

Episode 2: No More Inviting You 100 Points

(Image)

Direction: CRYTHIC’s daily life captured through the camera lens, their performance evoking third-person recollections. The ensuing Summer Triangle draws one in, yearning for an unreachable transcendence.

Script: RaNA’s abrupt interruption in Soyo’s conversation leaves a mark. The existential questions surrounding the nearly silent Tomori paradoxically multiply.

Friendship, terror, pop, and horror strike an exquisite balance.

Storyboard: The design of the deformed ANON reacting to a tongue click is masterful. Soyo’s terror as she silently accepts the message in the darkness.

Character Design: “We’re friends, right?” Soyo’s smile is terrifying.

Art: RiNG’s flowerbed is unnecessarily lavish.

Sound: Light piano even in RiNG’s flowerbed background. Illuminating the grim ANON and TaTsuki, Soyo’s faint smile.

OP: The A-melody begins under cloudy skies, clearing towards the chorus. Puddles remain, yet the umbrella closes.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Moving forward even through calculation

Tomori: The gaze of a boy dreaming of hope in the starry sky’s myths wavers between human connection

Tatsuki: Supported by direct feelings toward those they depend on

Soyo: Utilizing others’ calculations

Rana: Speaking through sound

Episode 3: 100 Points

(Image)

Direction: A mother’s lecture that reverses after childhood friendship. The acquisition and severance of daily life through music, achieved by the grown-up Tomori, is vividly portrayed through the disconnection brought by Haruhikage, stemming from the song “I Want to Be Human.”

Screenplay: The angelic design of Sakiko descending. The purpose of Molfonica’s revival is also glimpsed.

Storyboards: Words written in repeated notebooks reveal a disconnect with the world. Tomori’s design of spreading wings unfolds with Haruhikage,only to be abruptly severed by CRYTHIC’s dissolution. Invited by Hakunboku,

the encounter and parting with Sakiko marks the beginning of a grand journey of love, as the flower language foretells.

Character Design: Even her mother fails to understand this disconnect. Can’t smile as well as everyone else… Maybe something important is missing…

Art: Retro accessories at Hazawa Coffee Shop

Sound: Gentle piano playing a sermon

Music: The piano playing the song “I Want to Be Human” is sorrowful

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Absent

Tomori: Before sadness hits, I wish I could gather my tears and save them—so I don’t drift away from the world. I want to be human, to be true to my words.

I want something precious like everyone else has. If there was such a thing, it would be CRYTHIC.

Tatsuki: A middle schooler whose complex about his older sister explodes.

Soyo: The quintessential middle school girl who spreads charm and keenly senses others’ preferences.

RaNa: Absent

Episode 4: For Life? 90 Points

(Image)

Direction: The band is formed, yet the story stalls. Rana, thrown in as a catalyst, anticipates turmoil.

Script: The fleeting appearance of “Yamamisaki Kenjiro” and his masterpiece ‘Sasame Yuki’ on the blackboard—a metaphor for the slow progression of events, echoing Tanizaki Junichiro’s ‘Sasame Yuki’. Soya’s dual nature is reflected through the old and new bands.

Storyboard: Soyo and Sakiko chasing downhill symbolizes life’s trajectory.

Character Design: Soyo touching her hair conceals her unease.

Art: An unusually lush cucumber field.

Sound: Piano and flute dissonance heightens anxiety.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: The youthful naivety that believes talking will lead to understanding. Keeping promises on a tangible timeline

Tomori: A band for life, lost for life. The clumsiness of taking others’ words at face value

Tatsuki: Moving forward by projecting envy of her sister onto others

Soyo: Exploiting others’ anxiety. Clinging to Shouko

RaNa: Resonating with the fun, the music alone, for a lifetime

Episode 5: I’m Not Running Away! 100 Points

(image)

Direction: The recurring conversations on the overpass serve as a metaphor for boundaries and a thread confirming their relationship. “You’ll understand” carries a premonition of mutual incomprehension, while Soyo’s dark smile glows eerily. Tomori’s desperate attempts to persuade ANON, weaving words from written language, searching his heart while hesitating, squeezing out ethical words that shake emotions.

Script: ANON searching for reasons to escape practice contrasts with Tou fleeing from the end. “Tou’s poetry is my poetry. It made me feel like even someone like me could live.” Tatsuki’s monologue pierces the heart.

Storyboard: Tatsuki, who pursues essence through directness, contrasts with Soyo, who soothes while urging. ANON’s fish-eye composition, eyes rolled back as she collapses, portrays a lost soul cast off from the world.

Character Design: RaNa’s pursuit of music and the stances of the four are highlighted.

Art: The rugged guitar’s wear and tear is emphasized.

Sound: RaNa’s playing Haruhikage hint at ripples to come.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Conscious of her own frivolity, she fears becoming a boring woman. She rolls her eyes at “It’s always been like this.” Lost ethics were ethics that advanced while retreating.

Tomori: Though she stands up, she fears causing hurt. She weaves the reasons for her fear into words.

Unable to find words of encouragement, she urges a trip to the aquarium.

Tou desperately persuades ANON, weaving words from the heart,

words squeezed out while searching and wavering, ethical and emotionally stirring.

Tatsuki: Direct, so she pursues the essence.

Soyo: Soothes while urging the whole body. All words come from the darkness, superficialities across the window, mere appearances.

RaNa: Offers only fun and music.

Episode 6: Why Now? 95 points

(image)

Direction: RaNa’s overwhelming performance possesses a sense of speed that convinces both Tatsuki and the audience. Tatsuki’s outburst and the school competition with ANON center on the theme of speed.

Script: ANON confronts music for the first time, clashing with the serious Tatsuki. Sakiko unable to fully break away, casts a shadow.

Storyboard: Tomorimori’s vocal practice under the futon has a snub-nosed cat vibe. “I can’t be like Sakiko!” erupts. Ultimately, the “everyone” in “It has to be everyone” is CRYTHIC, and Soyo’s cut in the final scene resonates with unease.

Character Design: The agitated Tatsuki contrasts with the omnipotent Sakiko and his sister.

Art: The overpass is a place for negotiation, an outpouring of anxiety, and a boundary line.

Sound: The explosive intensity of “I can’t be like Sakiko!” is staggering.

Music: The demo feel and warmth of the Hekiten bansou via DTM.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Moving forward together, moving forward while lost. Straight ahead for others.

Tomori: Moving forward even if awkward and clumsy, flailing about in bed.

Tatsuki: Confronting composition, aiming to break away from her sister. The normalization of raw emotion is the flip side of anxiety.

Soyo: Pretending to be a good girl causes both emotions and true feelings to become lost.

RaNa: Music alone.

Episode 7: Even After Today’s Live Ends, 100 Points

(image)

Direction: Tatsuki warned from the outset, RaNa starting to play on her own, Tomori’s raspy voice layering anxiety—foreboding of impending ruin.

Script: Disruption at the beginning, the unease of the live camera, the three initial failures accumulating like dust toward the final collapse.

Storyboard: Tomori unable to shake her fear of the live performance, the live camera perspective vividly capturing daily life and foreboding anxiety—a path leading to collapse.

Sakiko glares at Tomori’s raspy voice, silently urging her on. Sakiko and Soyo gasp at the intro to “Haruhi Kage,” their challenge to nostalgia inducing shivers. Sakiko bites her navel, her voice trembling as she dashes from the venue. Soyo, head bowed, desperately holds back her emotions, contrasting sharply with the other members on stage.

Character Design: Tatsuki’s consideration in viewing the entire cast reflects growth

Art: The escalating unease from the live camera creates a superb effect

Music: Hekiten bansou encouraging ANON ultimately bathes her in a halo. Haruhikage makes everyone but Soyo shine, makes Soyo groan, makes Sakiko run wild, and creates myth.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: She doesn’t hide her lack of confidence in apologizing with a smile.

Tomori: She’s honest with her emotions but lacks the capacity to consider others. She can’t string words together without genuine feeling, and even during performances, her first voice won’t come out. Only during the chorus of “I’m Trying My Best” does the staging finally align her emotions with her thoughts.

MC: “I thought, ‘I hate bands, I want to quit.’ But all I can do is try my hardest.

My poetry is the cry of my heart!” A Rousseau-esque theory of language origins, remaining faithful to language.

Yet her excessive fidelity to the abstract (language) carries the danger of its inherent ambiguity (diverse interpretations).

Tatsuki: Growth capable of caring for others.

Soyo: While appeasing the surface, she explodes from her own boundaries, becoming lost in faith.

RaNa: Simply weaves the sounds she loves as she pleases.

Episode 8: Why? 100 Points

(image)

Direction: Sakiko and Hatsuka pull Soyo back from outer space to reality and aspiration. Soyo’s white eyes tremble as she plays the facade.

Clinging to Sakiko, trembling at Mutsumi’s denial, unable to accept the present, Soyo literally drifts in fiction.

Script: CRYTHIC, Sakiko, Mutsumi. Soyo, obsessed, tosses both the band and emotions about.

Storyboards: Eyes gleaming on obsidian search for Tomori’s words. The dark Soyo crouching under blankets, relentlessly sending messages, is terrifying.

Character Design: Emphasizes Sakiko’s faint presence within the school.

Art: An excessively tidy room mirrors Tomori’s autistic tendencies. Water lilies reflect the rise and fall of CRYTHIC and Sakiko.

Sound: Hypocrisy rendered thick and sorrowful through violin

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Concerned about Tomori’s relationship with the members

Tomori: If things stay like this, everyone will drift apart. I don’t know what hurt them, but I want to convey my words.

Tatsuki: Becomes oblivious to others’ feelings because he sacrifices himself for Tomori and music

Soyo: Can’t control her emotions because she’s too eager to please Sakiko

Rana: Won’t move without music

Episode 9: Disbandment

100 points

Heartbreaking

(image)

Direction: Tatsuki’s words to Tomori dance through the sky from above. Tatsuki’s desperate grasp and Soyo’s expressionless, cold words take your breath away.

Tatsuki’s runaway exposure and Tomori’s inability to hold back ANON—“I don’t want this anymore… I never wanted to be in a band…”—leading into the ED sequence “What even is ‘normal’ or ‘ordinary’?” is so intense it leaves you speechless.

Screenplay: The Soyo household begins with divorce scenes from the start. Even during CRYTHIC’s founding, Soyo acts as the behind-the-scenes organizer, yet she is actually the most dependent.

Storyboards: Soyo’s obsession with CRYTHIC and glimpses of her madness are well portrayed. “It’s okay now.” The lie visible by the window feels doll-like.

Character Design: The dissonance between Soyo’s career-driven mother’s youthful maternal aura and the grown-up Soyo shines in the shadows.

Art: The mirror in the practice room creates distance between body and psyche.

Sound: The piano during Soyo and Tomori’s parting feels utterly severed.

Music: Standing helplessly, at the mercy of events.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Caring for members stems partly from Soyo inviting me. The presence or absence of relationships and belonging directly shapes my straightforward words and actions.

Tomori: Prone to falling into a negative spiral where others’ words push responsibility onto me. Overly sensitive to what others say.

Tatsuki: Lack of interest in anyone besides Tomori borders on excessive sincerity.

Soyo: The fear of suppressing my true feelings while playing the role others expect. Her desire to support her mother inverts into CRYTHIC. The obsession “It’s not disbandment” drives her. The hair she constantly touches is the beginning of self-love.

RaNa: Absent

Episode 10: Lost Forever 100 Points: (You might Wailing)

(image)

Direction: The first half erupts with an intense, almost demonic tension. Tomori’s frenzied poetry live performance, her repeated pleas to ANON, ANON’s persuasion of Soyo, the build-up to the live show—everything is polished. Tomori sings her poetry as if appealing not to the audience but to the band members themselves, her words stTatsuking Tatsuki, ANON, RaNA, and Soyo as a semantic force beyond language. Emotions transcending words resonate with the audience through the members. In contrast, Mutsumi’s expressionless face illuminates her subsequent, even more “unhuman” perspective.

Script: Rising from complete ruin, conveying not words but feelings. Until it’s understood, until it reaches them.

Tou’s feelings, her words, her every action draw the viewer in, shaking their empathy.

Storyboard: Mutsumi’s initial dissonance is juxtaposed with Soyo, becoming a path to Tou. The poetic monologue, the metaphor of escape into space through Uika and the planetarium, is resolved in the conversation immediately following. Finding the North Star, confirming one’s position.

After Tōmori’s repeated pleas, ANON bites her lip and runs away. The part where she looks up at the sky severs her lingering resentment along with her resignation.

ANON’s persuasion of Soyo makes her eyes narrow as she slams her cup down, Soyo standing tall.

Their navel-gnawing, in the live scene, renews its meaning as an unbearable longing for poetry that lies beyond words. The navel-biting of anger and regret is driven out by poetic language as a precursor, transforming into navel-biting that restrains overflowing emotion with reason.

Character Design: In the shadow of the light, MVP RaNA-na is actually crucial. It’s feeling over words, action, and the impulse born of being undifferentiated. Mutsumi’s lead-in to Soyo is also subtly important.

Art: The cloudy sky chasing after ANON also stagnates.

Sound: The music box’s gentleness feels rather melancholy. The background sound played in the guitar part from RaNa’s joining serves as a path to the live performance.

Music: Poetic language as a pioneering impulse preceding words. The poem of light woven from the opening, transforming many times, sutured together,

culminates in the lyrics of “Uta kotoba” and the band’s individual parts.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Consideration for others and responsibility are the source of our words and actions.

Tomori: Not conveying words, but conveying feelings. Until it’s understood, until it reaches its destination. Poetic language that transcends words is Le Sémantique

Tatsuki: Both my reflection on Tomori and Tomori’s poetry are important

Soyo: “I’ll end it,” those eyes are powerful. And what I truly wanted to end was the part of myself I couldn’t reveal—this is silently revealed through the live performance

RaNa: Honest about fun, music, and words

Episode 11: Even So, 90 Points

(image)

Direction: Sparse applause reflects true emotion. A place to belong is created by someone else, or by oneself. A lifetime is difficult, but perhaps a lifetime is built by accumulating moments.

Script: The Butterfly Dream, based on Zhuangzi, reflects a reality where dreams and reality melt together. Spring sleep knows no dawn overlays the background of a lamp burning late into the night.

Storyboard: Emphasizes the four members’ emotional confirmation after the dark stage and RaNa’s solo. Increases the number of in-between gags for a stark contrast to the previous episode. Highlighting Soyo’s sullen expression as she posts on SNS. The final 2D storyboard of sleeping members incorporates a motif of ascending to heaven.

Character Design: Each member’s stance stands out more prominently.

Art: The blur in the group photo and everyone facing different directions evokes a sense of being lost.

Sound: Daily life emerges and shatters through the sound of crushing deep-steamed green tea candy. Features a comical tempo.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Increasingly reckless toward members, more intervention with Soyo

Tomori: Will do it for life even if used. Her stubbornness has a core. Though a lifetime without hurt is impossible, she’ll struggle and suffer, rise up, and want to do the band

Tatsuki: His clumsy way of acknowledging ANON and his solitary DTM studies both show sincerity. The beginnings of a leader emerge.

Soyo: Her detached gaze and attitude remain consistent. Yet she observes Tou’s behavior. Her blatantly self-loathing attitude is her true self.

RaNa: “I was moved.” Those words carry weight.

Episode 12: It’s My GO!!!!! 100 Points

(image)

Direction: ANON, unable to confirm completion, and RaNa standing frozen—a profound sense of being lost from the very start. The live part’s rigging weaves music, lyrics, and audience members in every direction. It’s okay to be lost, keep moving even while lost.

Script: It’sMyGO!!!!! The position where she proudly declares “It’s my turn!” is way too conspicuous lol. In stark contrast to the spectacular live part, the members of the new band AveMujica, who are redrawing the path, reflect the parting ways alongside the cucumber return.

Storyboard: AfterGlow’s red and MyGO’s blue are contrasted. Umiri and Mutsumi, standing as audience members, confirm the current situation. The hotel contrast between the upwardly mobile Nyamu (Wakamugi) and the fallen Shoko reflects their present positions while foreshadowing Mutsumi’s grim fate, already being used as a bargaining chip.

Character Design: Soyo finally reveals herself with a smile in the final moments of Mayoi uta. “Thank you for not letting go,” whispers Soyo, groaning.

Art: The entrance area and interior of the hotel café are elegantly furnished.

Sound: The excitement of the live performance and the unsettling twist in the finale are the true essence of classical music, which is characterized by modulations.

Music: Don’t recommend the bright future of Mayoi Uta. The audience shown singing is the viewer—yourself.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: That reckless abandon actually stands tall only beside Tomori.

Tomori: I want to tell her how grateful I am she’s here. I almost cry thinking of my gratitude to Soyo. We hurt each other, we fight, but we’re here. Never leaving, words trembling.

Tatsuki: Remarkable growth in gradually caring for and uniting the members.

Soyo: In contrast to Tatsuki, exposing oneself and releasing thorns is also the ethics of the lost.

RaNa: Without speaking, strumming her own self through the guitar’s song.

Episode 13: The Only One I Can Trust is Myself 95 points

(image)

Direction: The opening scene with part-timer Shoko reflects the predicament from the previous episode’s climax. After the MyGO!!!!! wrap party and AveMujica’s live performance, the final line “I’m home, you bastard father” serves as a perfect cliffhanger for the next episode and the birth of a new mystery.

Script: Mutsumi still can only speak directly and bluntly, even to someone who should be her best friend. AveMujica’s narration part is both a metaphor for SNS society—abandoned by its owner, destined to be someone else’s plaything tomorrow—and the idol itself.

Storyboard: “The weak me is already dead,” Sakiko’s feigned toughness is rather melancholy and forlorn. MyGO!!!!! finally enters its daily life segment, signaling the finale. The contrasting shift to AveMujica, gradually building an unsettling atmosphere, hints at the dark entrance to the impending second half (“AveMujica”).

Character Design: The weight of Soyo’s confession, facing her raw self and revealing the unforgettable CRYTHIC; the monologue “It’s pretty bad, you know” is intense.

Art: The surging planetarium reveals Hatsuka’s current location. Sakiko’s repeated presence before the mansion contrasts with the poor’s present.

Music: AveMujica. A simple stage where thorns and the AveMujica crest emerge within a labyrinth of red moon and red gate. The dolls’ masquerade ball is merely the prologue to the end.

Lost Ethics)

ANON: Having a band-aid placed on my heart, words of gratitude are an affirmation of playing in the band for life, a resolve to move forward while hesitating in each moment.

Tomori: Moments accumulate to become a lifetime.

Tatsuki: Already the organizer, having grown enough to gently scold ANON.

Soyo: Speaking to Tomori on the overpass, her pain at Tomori’s raw lyrics is genuine.

RaNa: The moment she nods to a lifetime is her true self.

Addendum) Theatrical Version “BanGDream! It’s My GO!!!!! Spring Sunlight, Lost Cat”

Re-watched upon Blu-ray release 2025.11.06, as notes.

・The sharp contrast between the owner discovering the real thing and the sunset is beautifully compelling and persuasive.

・The RING guitar arpeggio accompanying RaNa’s loss and recovery of her place,

its mellow, chic melody line expressing sorrow and joy in a sentimental way

・The light of a sharp sensitivity to words is reflected back, revealing that she doesn’t like the object itself, but the act of finding it

・Tatsuki’s intimidating, aggressive demeanor is inserted comically, creating an interesting rhythm of tension and release.

・The beautiful contrast of the aquarium’s aerial penguins against the sunset and azure-pink hues encourages ANON, who freezes in fear after being called out for her self-conscious pretense and escape from band activities.